I used to have ghost stories. Someone asked me once if I'd ever seen a ghost. "Oh, yes," I remember saying. I was in possession then of vivid details about what I'd seen. I lost those stories when my son was born. It was like the act of giving birth erased them from my body and mind. I don't remember the ghosts. I'm haunted by other things now.

*

At a neighborhood Halloween carnival, my friend oversees the Build and Draw booth, where she has laid stacks of moving boxes against the schoolyard fence. There is multi-colored heavy-duty tape, zip ties, scissors. Of their own volition, the children have built a facsimile of the Brooklyn Bridge. They have crafted arches and hung cables. They do not draw pedestrians, only birds and ghosts lingering on the limestone towers. Only birds and ghosts. It's an abandoned bridge. It's in the future, one child tells me.

*

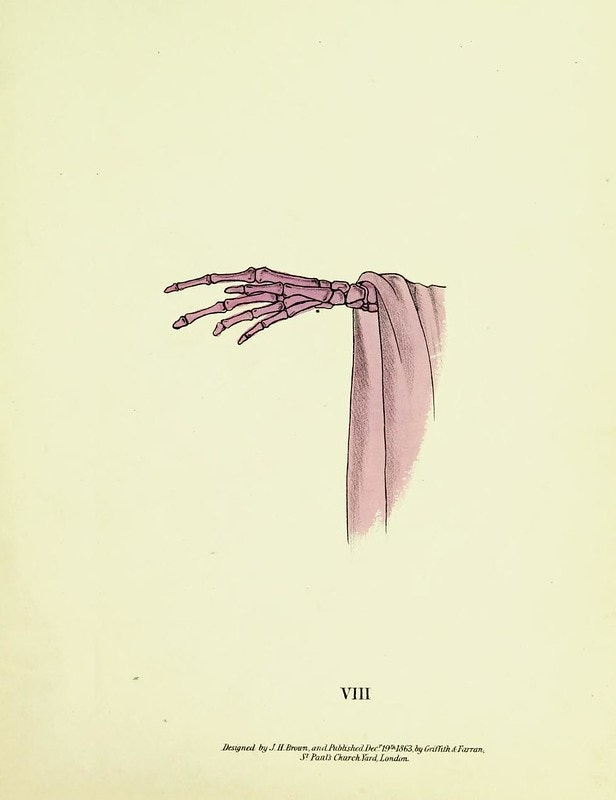

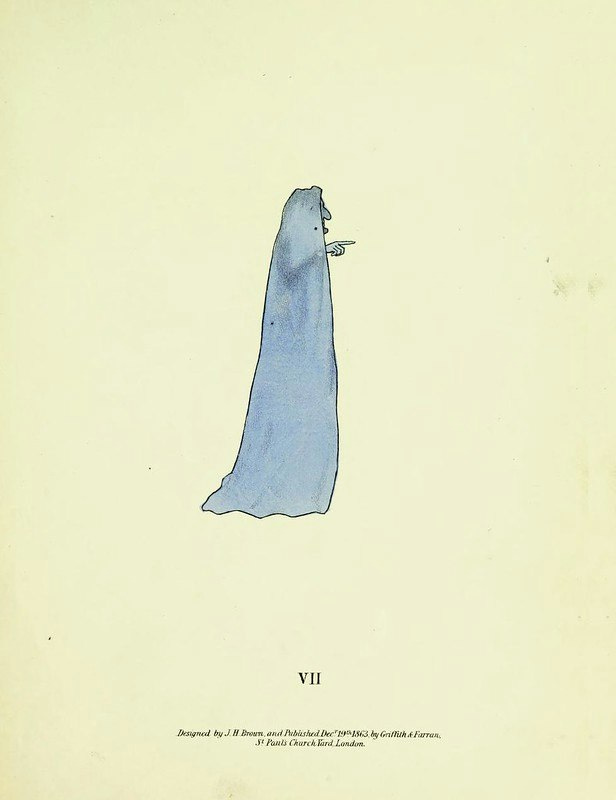

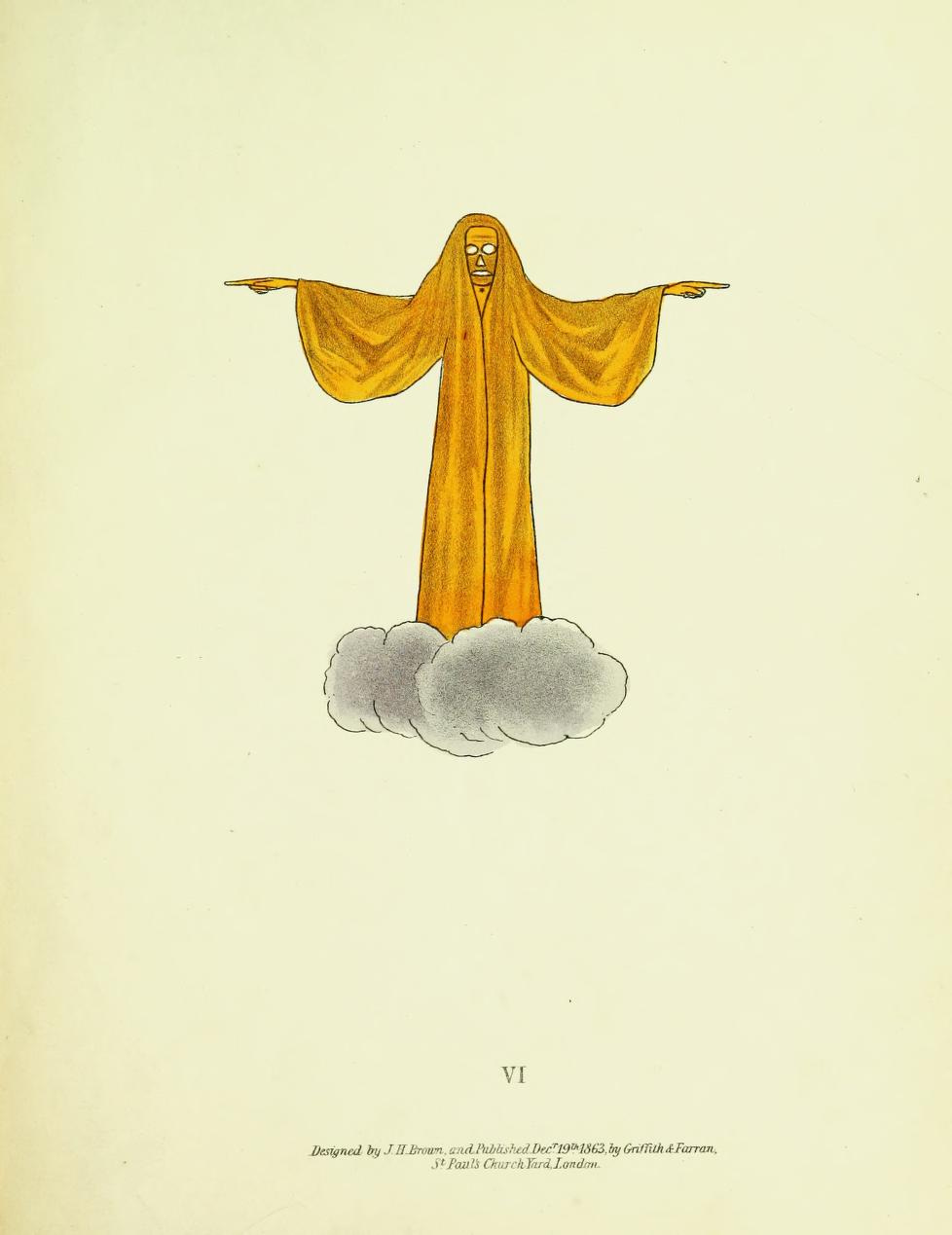

Spectropia or, Surprising spectral illusions: Showing ghosts everywhere and of any colour is a collection of mostly hand-painted lithographed plates by J.H Brown, first published in 1864. I've only ever seen it in the Internet Archive. The printed book is bound in cloth an eerie shade of Paris green, an arsenic-based paint so toxic that farmers in Indiana discovered it could be used as an insecticide.

*

There is an essay by Claudia Dey called Mothers As Makers of Death. She writes about the "sudden crushing morbidity filling the new mother's soul." I think of this essay often, especially around Halloween, especially when I'm asked why my writing is so concerned with mortality.

*

At the neighborhood Halloween carnival, someone's dad plays DJ, blasting "Bette Davis Eyes" across the courtyard. My son pulls me toward the Haunted House, a structure made of wood and industrial-grade black garbage bags, the entrance of which is a Hellmouth, the toothy gob of an infernal clown made with painted cardboard and styrofoam. Someone else's dad ushers us into the cavity in groups of ten. Another dad inside is dressed as a bloodied chef. We are in his kitchen. It is dark. Dad Number Four is shuffling around dressed as a clown and wearing an apron, curious sous, and running his rubber-gloved hand through a bowl of dry ice. The chef is clutching a severed hand and waving it at the children, saying, "This was my best friend." He asks if we are hungry. "What's in my freezer?" He opens the door. Another dad reaches a hand from behind more dry ice and moans. "What's in my sink?" Another dad is there, ready to pop his head out from the dirty dishes. There is a dad, also, in the oven and another behind the children, unnoticed until he screams to frighten us back out the direction we came. The dads will do this from 12pm until 4pm, when they will go together to Bar Great Harry after only a performative attempt to remove the fake blood and perhaps collectively begin to wonder how many children exited the clown's mouth looking like they had seen something they should not.

The lithographed plates in Brown's 1864 book are of ghostly figures—winged Victory, skeletons, a cloaked figure with a broom, faces peering out from shrouds. The viewer is instructed to find the asterisk on each plate and concentrate on it, staring at it for 20 seconds, then turn to a wall to see the specter floating before them. Brown writes, "...the spectre will soon begin to make its appearance, increasing in intensity, and then gradually vanishing, to reappear and again vanish; it will continue to do so several times in succession, each reappearance being fainter than the one preceding."

*

Something small I know about horror: In May this year, a writer I love named Katie Gutierrez wrote a piece for Time called Raising Children in America Means Living in Fear That They'll Be Shot. She opened the piece with the story of the toddler in New York City who was killed when a loose brick fell from a neglected building facade. Two years ago, I referenced this same child and the tragic accident that killed her in an essay I wrote for The Rumpus about parenting, climate grief, and gun violence. It is the randomness the mothers fear—randomness of luck, randomness of violence. It sends us looking for patterns.

*

It is morning, and my son spins around the park through clumps of bright orange leaves. It is not even 7am yet. Any adventures we have before the school day are small—a shared everything bagel, looking at seasonal decorations on pharmacy shelves, walking on Clinton Street instead of Court. To take his bike out two whole hours before school begins is a treat, and his face shows it. I walked to the park with a cup of coffee. My son asks if I will chase him.

I rest my coffee on a bench and remove my coat. I'm wearing a baseball cap and old sneakers. I'm faster than he wants me to be. He wants to play Sleepy Hollow. He's Ichabod Crane, and I'm the Headless Horseman. I pretend I'm on horseback and pull my cap down over my face. I am the ghost of a Hessian soldier decapitated by a cannonball, galloping after a child's green bicycle.

*

The figures produced by the lithographic plates in Spectropia, the ghosts appearing on the wall, result from an afterimage, a visual disturbance during which activity in the retina causes images to remain on the eye even after the original stimulus is no longer in front of the viewer. A period of exposure to an image can cause it to remain with us. We can haunt the houses ourselves.

*

At least once a week, one of my children asks what they'll do without me when I die. The sweaters my mother sends for my children hang by the front door. I bury my face in these sweaters when I'm alone. In the mornings, I help my children pull their arms through knit sleeves. When I help with the buttons, I try to be slow. I kiss my children’s cheeks again and again. I kiss the buttons, too. For luck. For protection.

*

I read once about apple divination on Halloween. Use a knife to peel the apple into one long ribbon, then toss it over your shoulder. The apple peel will reveal an initial, a name, a blessing, a warning. Or light a candle and eat an apple while looking in the mirror. Someone will appear before you in the mirror, delivering a message about your future.

We're all looking for something to be revealed, and the perceived thinness of the veil might allow some information through—and who we will love, who will love us, how we will live, when we will die.

We are walking down Henry Street, my children and I. I love everything about this season. But this year, a neighbor's Halloween display is so gruesome I fight a wave of nausea as we pass. There are bloody limbs everywhere and a plastic body wrapped in a plastic sheet. Elsewhere in the neighborhood, someone has draped a blood-stained nightgown in their garden. Decoration. My jaw gets tight. We avert our eyes. We tell our children it isn't real.

*

With his optical illusions and the accompanying scientific illustrations of the human eye, Brown was trying to combat the rise of Spiritualism, a movement gaining popularity in the United States when he was writing. Did people stop hosting seances in their living rooms after discovering Brown's book? Did scientific explanation about the rods and cones of the eye stop anyone from reaching again for the spirits?

*

In the chapel at Green-Wood Cemetery is a community altar, an installation called Mictlan by Cinthya Santos-Briones. This is the fifth year the cemetery has commissioned an artist to create a large-scale community altar, a practice of reverence and connection I didn't know I needed. All of us looking for answers. All of us looking to give space to our celebrations and our grief. Looking to do it together.

I am standing alone in the chapel with my daughter. There are bottles of whiskey. Candies. Flowers. Art and photographs. Here is who is gone. Here is who we have loved. Here is what we are left with. There are notes and candles. Tonight, there will be names on the altar. Lists of children. And this is the horror the mothers carry—the children, the children.

Someone has placed a votive on top of an envelope. The candle has been burning for some time. The envelope reads, "I love you." My daughter takes my hand as the flame flickers out.

So incredible and thought provoking ✨you captured the hauntings of morality in motherhood perfectly

Incredible writing. <3